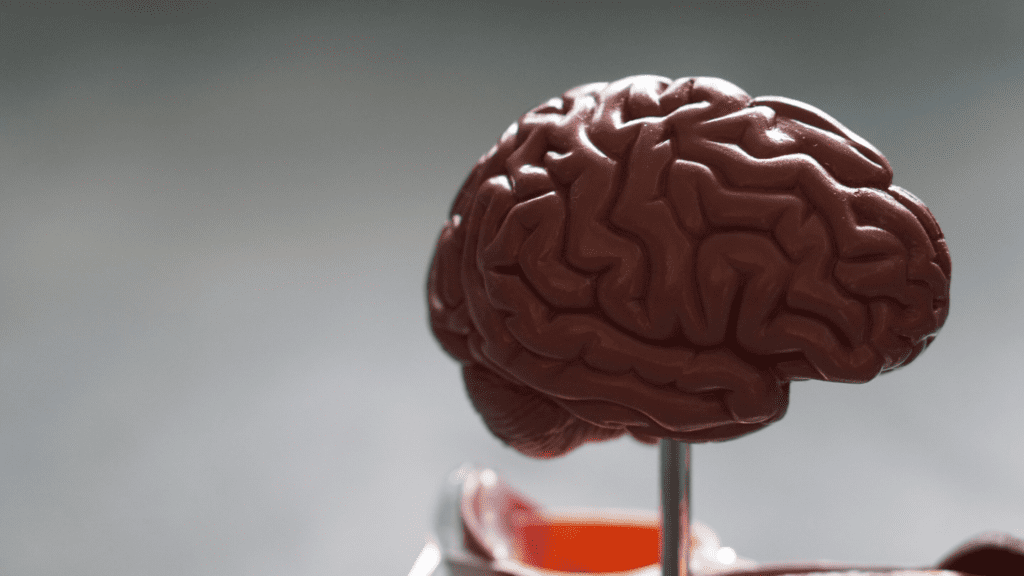

Brain Variation, most people want to avoid discomfort, but some, particularly adolescents and young adults, can inadvertently cause bodily harm. Self-harm is strongly linked to other mental health conditions such as anxiety and depression, but not everyone suffering from such a condition engages in self-harm.

“We’ve long attempted to understand how persons who self-injure differ from others and why pain alone isn’t a sufficient deterrent,” says Karin Jensen, researcher and group head at Karolinska Institutet’s Department of Clinical Neuroscience and the study’s corresponding author. “Previous research has revealed that persons who self-harm are less sensitive to pain in general, although the reasons underlying this are not entirely understood.”

Pain tolerance increased

The current study compared pain modulation in 41 women who had engaged in self-injury at least five times in the previous year to 40 matched women who had not engaged in self-injury behaviour. The women, aged 18 to 35, were subjected to laboratory pain tests at Karolinska University Hospital twice in 2019-2020, during which they were asked to rate the pain they felt from transitory pressure and heat stimulations. MRI scans were also used to examine their brain activity during pain.

The researchers discovered that self-harming women withstood more pain than controls on average. Brain scans revealed changes in activity between the groups as well. When compared to controls, the brain activity of women who self-injure showed stronger connections between brain areas directly engaged in pain perception and those linked to pain regulation.

Another finding was that the difference in pain modulation was unrelated to how long, how frequently, or in what way the participants participated in self-injury.

Knowledge that is clinically applicable

“Our findings show that efficient pain modulation is a risk factor for self-injury behaviour,” says Maria Lalouni, a researcher at Karolinska Institutet’s Department of Clinical Neuroscience and the study’s joint first author with Jens Fust, who recently completed his Ph.D. on the subject. “It also informs us more about the variations in the brains of people who self-injure, knowledge that may be used to improve the assistance provided to persons seeking therapy for their behaviour, as well as in dialogues with patients to help them comprehend their self-injury and the need for treatment.”

The study’s limitations include the fact that women who self-injure reported greater psychiatric comorbidities than controls. They also used more medicines, such as antidepressants, which the researchers took into account.