Caltech’s, in everyday situations, we tend to take our sense of touch for granted, although it is critical for our capacity to interact with our surroundings. Consider reaching into the refrigerator for an egg for breakfast. When your fingertips touch the egg’s shell, you can detect how cold it is, how smooth its shell is, and how tightly you must grip it to avoid crushing it. These are skills that robots, especially those controlled directly by humans, can difficulty with.

Caltech’s innovative artificial skin can now offer robots the ability to sense temperature, pressure, and even dangerous compounds with a single touch.

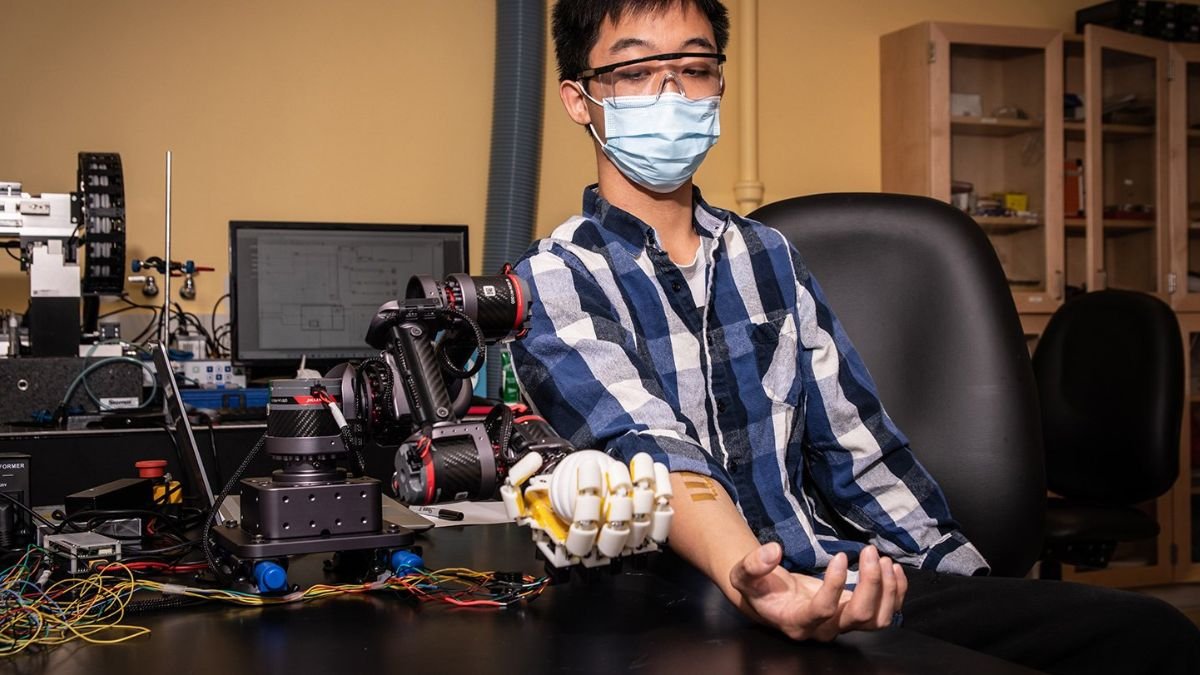

This new skin technology is part of a robotic platform that also includes a robotic arm and sensors that attach to human skin. A machine-learning system that connects the two enables the human user to direct the robot with their own movements while receiving feedback via their own skin. The M-Bot multimodal robotic-sensing platform was created in the lab of Wei Gao, a Caltech assistant professor of medical engineering, Heritage Medical Research Institute investigator, and Ronald and JoAnne Willens Scholar. Its goal is to provide people with more precise control over robots while simultaneously protecting humans from any risks.

“Modern robots are becoming increasingly vital in security, farming, and industry,” Gao explains. “Can we imbue these robots with a sense of touch and temperature?” Can we also teach them to detect substances like as explosives and nerve agents, as well as biohazards such as pathogenic bacteria and viruses? We are working on it.”

The epidermis

A comparison between a human hand with a robotic hand reveals significant differences. Robotic fingers are hard, metallic, plasticky, or rubbery, whereas human fingertips are soft, squishy, and fleshy. The printable skin produced in Gao’s lab is a gelatinous hydrogel that makes robot fingertips more human-like.

The sensors that allow the artificial skin to monitor its surroundings are embedded into the hydrogel. These sensors are physically printed onto the skin in the same way that text is printed on a sheet of paper by an inkjet printer.

“Inkjet printing has this cartridge that ejects droplets, and those droplets are an ink solution,” Gao explains. “However, they could be a solution that we develop instead of regular ink.” “We’ve created a number of nanomaterial inks for ourselves.”

After printing a scaffolding of silver nanoparticle wires, the researchers may then print layers of micrometer-scale sensors capable of detecting a range of objects. Because the sensors are printed, the lab can design and test new types of sensors more quickly and easily.

“When we want to detect a specific substance, we ensure that the sensor has a high electrochemical response to that compound,” Gao explains. “Platinum-impregnated graphene”

detects TNT explosives rapidly and selectively For a virus, we are producing carbon nanotubes with a high surface area and attaching antibodies to them. All of this is mass-producible and scalable.”

A system that is interactive

Gao’s team has linked this skin to an interactive system that allows human users to manage the robot using their own muscle movements while also receiving feedback from the robot’s skin.

This section of the system employs extra printed components, in this case electrodes attached to the human operator’s forearm. The electrodes resemble those used to monitor brain waves, but they are positioned to detect electrical signals created by the operator’s muscles as they move their hand and wrist. A simple flick of the human wrist causes the robotic arm to move up or down, and clenching or splaying of the human fingers causes the robotic hand to do the same.

Gao explains, “We applied machine learning to transform those signals into movements for robotic control.” “The model was trained on six different gestures.”

In addition, the device offers feedback to the human skin in the form of extremely light electrical stimulation. Using the egg as an example, if the operator grips the egg too tightly with the robotic hand and risks cracking its shell, the system will inform the operator with what Gao described as “a small tickle” to the operator’s skin.

Gao hopes that the system will find applications in agriculture, security, and environmental protection, allowing robot operators to “feel” how much pesticide is being applied to a field of crops, whether a suspicious backpack left in an airport has traces of explosives on it, or the location of a pollution source in a river. But first, he wants to make some improvements.

“I believe we have demonstrated a proof of concept,” he says. “However, we aim to improve the stability of this artificial skin in order for it to live longer.” We expect that by improving new inks and materials, this can be used for many types of focused detections. We want to put it on stronger robots to make them smarter and more clever.”

The research paper, titled “All-printed soft human-machine interface for robotic physicochemical sensing,” will be published in the June 1 issue of Science Robotics. Medical engineering graduate students Jiahong Li, Samuel A. Solomon, Jihong Min, Changhao Xu, and Jiaobing Tu are co-authors, as are postdoctoral scholar research associate Yu Song, previous postdoctoral scholar research associate You Yu, and visiting student Wei Guo.