The prognosis for ovarian cancer patients is bleak: less than half of patients with high-grade serous ovarian cancer (HGSC) survive five years after diagnosis. Tumors typically respond well to chemotherapy at first, but become resistant after repeated treatments, allowing cancer to reoccur. Researchers from the University of Helsinki, the University of Turku, and the Turku University Hospital investigated how these tumors develop resistance to chemotherapy in a study. They investigated how tumors changed during chemotherapy and discovered a new cancer cell state linked to poor treatment response.”Our research design is exceptional, even globally, and necessitates close collaboration among clinicians, computational researchers, and biologists.” It is also critical that the vast majority of patients see cancer research as valuable and choose to donate their samples for research purposes,” says University Researcher Anna Vähärautio, the study’s corresponding author from the University of Helsinki.

“These unique paired tumor specimens were collected at Turku University Hospital by our clinical partners, led by a gynecological oncologist, MD Ph.D. Johanna Hynninen.” To fully exploit these samples, we used a new analysis approach developed by researchers in Professor Sampsa Hautaniemi’s group, particularly by Ph.D. student Kaiyang Zhang (first author of the study), which allowed us to investigate what unites the tumors rather than analyzing specific features of each tumor. “We were able to identify similar, chemotherapy-induced changes in gene expression at the level of individual cells across this heterogeneous set of tumors this way,” Vähärautio explains.The findings were published in the prestigious journal Science Advances0

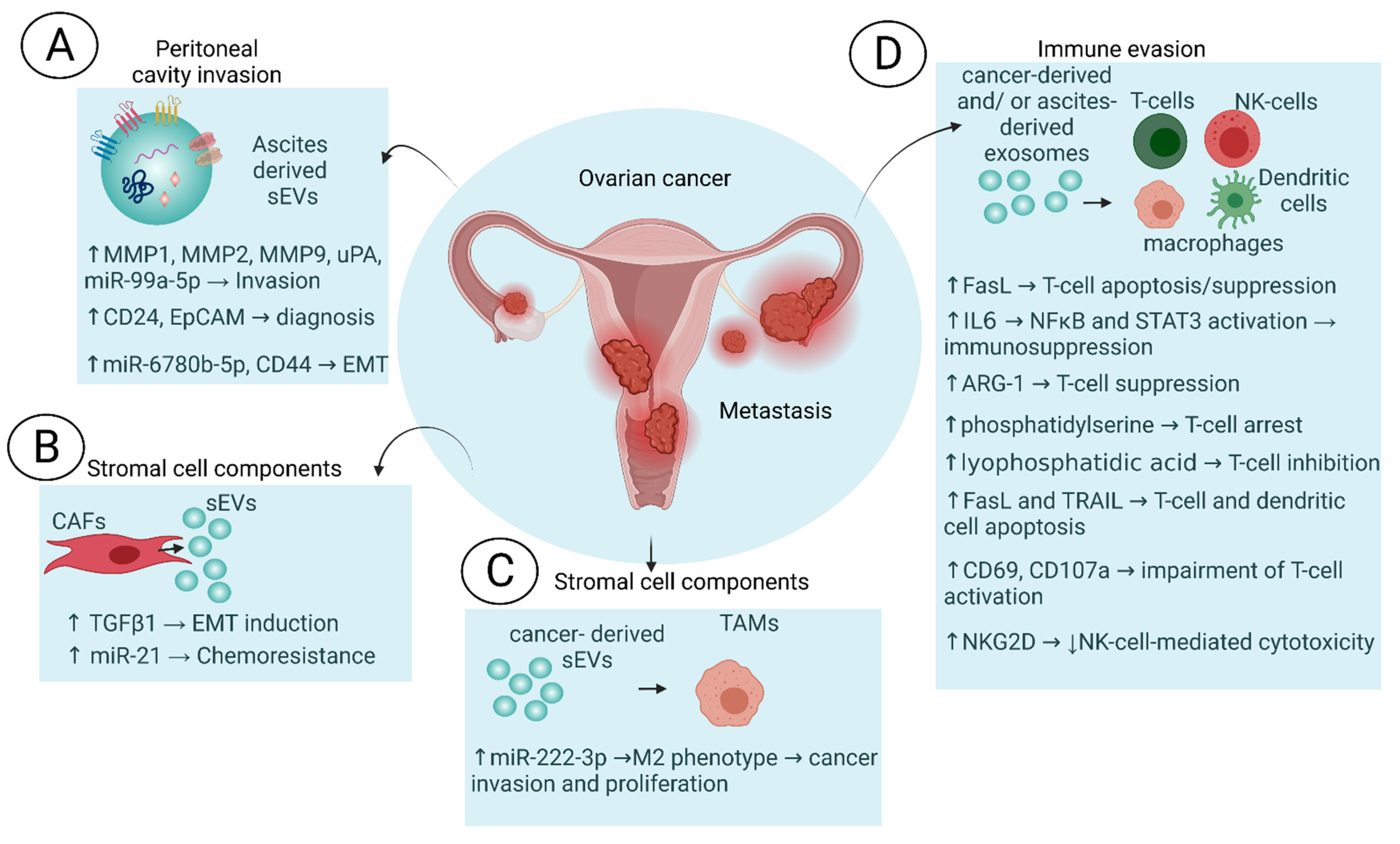

.Chemotherapy induced a state of stress in cancer cells.Chemotherapy increased a stress-related state in cancer cells, according to the findings. The tumor subclones that were in the most stressed state prior to chemotherapy were enriched during treatment. This was due to the fact that these high-stress subclones restarted growth more robustly after chemotherapy than other clones, repopulating the tumors more effectively.”Our findings are also supported by a larger international validation cohort of 271 ovarian cancer patients, in which a higher stress state in the tumor prior to chemotherapy predicted significantly worse treatment response,” Vähärautio says.The cancer cell stress state was linked to the composition of the tumor’s microenvironment in the study. The inflammatory stroma was especially abundant in high-stress tumors. Both cancer cells and the stroma produced a large number of signaling molecules in these tumors, which have the potential to further strengthen the inflammatory stress state on both cell types. This vicious cycle of inflammatory signaling has the potential to reduce the tumor’s response to chemotherapy.