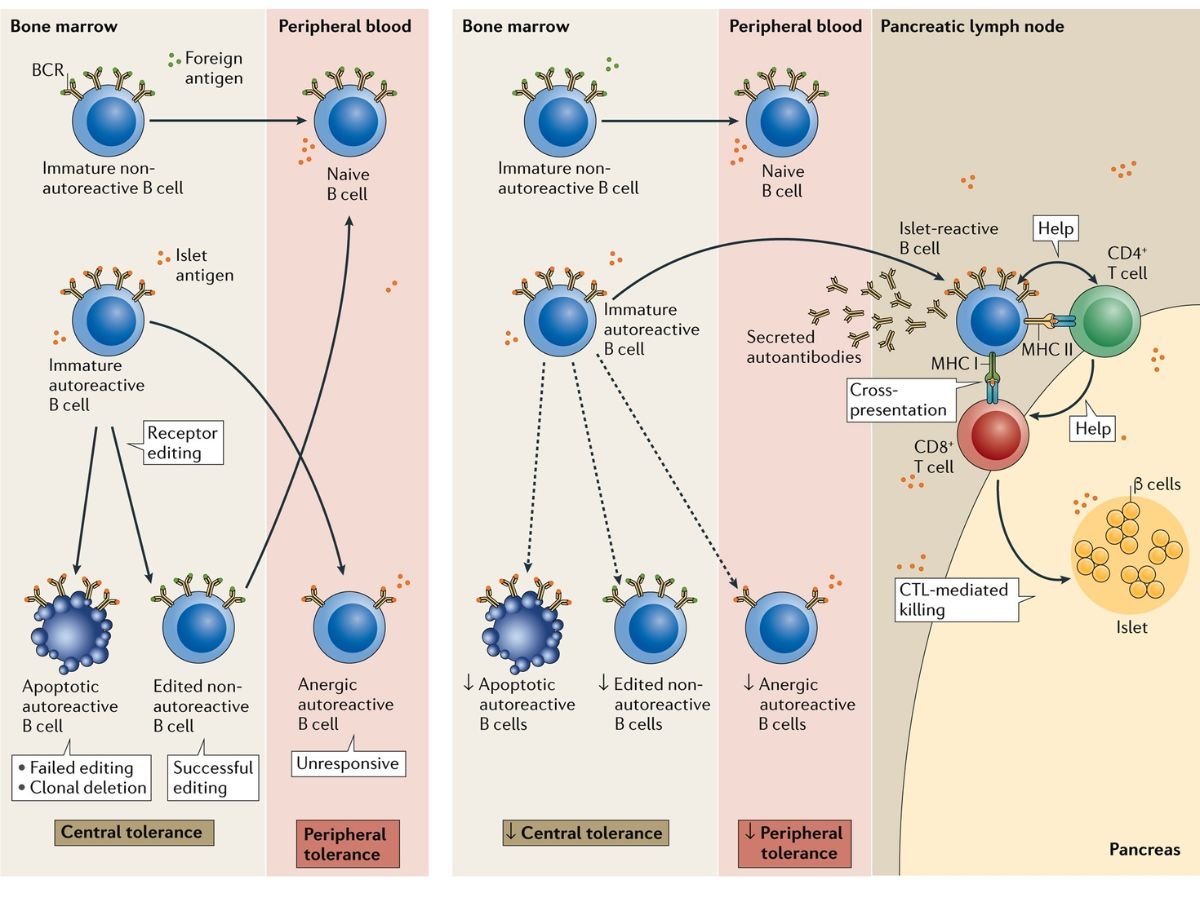

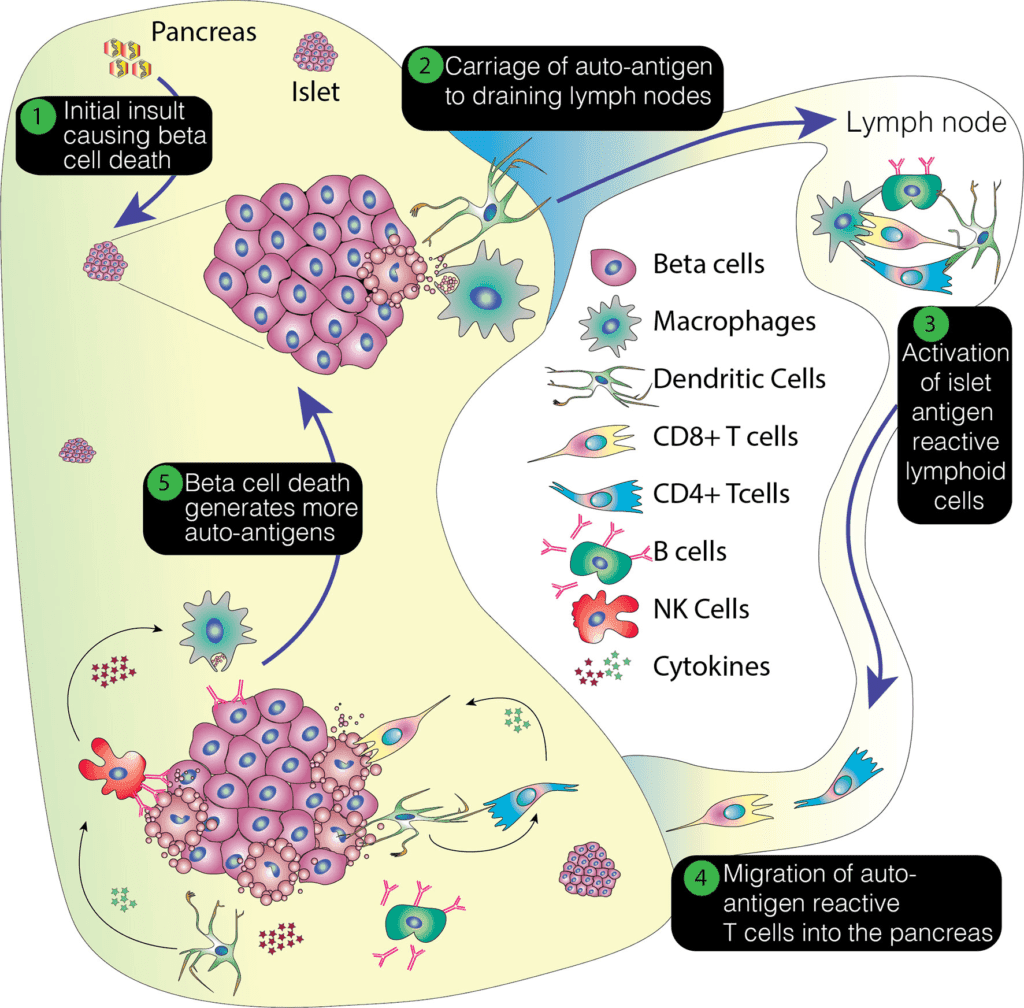

The autoimmune response, in which the immune system destroys pancreatic islet beta cells that make insulin, is often the focus of research into the origins of type 1 diabetes. A recent study from the University of Chicago instead focuses at the role of beta cells in causing autoimmunity. The study also suggests that new drugs could prevent the immune system from killing beta cells, preventing type 1 diabetes in at-risk or early-onset patients.

The study, which was published today in Cell Reports, details how the researchers utilised genetic tools to knock out or delete a gene called Alox15 in mice who are genetically prone to type 1 diabetes. This gene encodes an enzyme known as 12/15-Lipoxygenase, which is implicated in mechanisms that cause inflammation in beta cells. Deleting Alox15 in these mice conserved their beta cell count, reduced the number of immunological T cells entering the islet milieu, and avoided the development of type 1 diabetes in both males and females. These mice also had higher levels of expression of the gene producing PD-L1, a protein that reduces autoimmune.

“The immune system doesn’t spontaneously decide to assault your beta cells one day.” “We hypothesised that the beta cell has fundamentally changed itself to attract that immunity,” said senior author Raghavendra Mirmira, MD, Ph.D., Professor of Medicine and Director of the Diabetes Translational Research Center at UChicago.

“When we removed this gene, the beta cells no longer signalled to the immune system, and the immune onslaught was entirely suppressed, despite the fact that we didn’t touch the immune system,” he explained. “This demonstrates that there is a sophisticated dialogue going on between beta cells and immune cells, and that if you intervene in that discussion, you can avoid diabetes.”

The research is the outcome of a long-term partnership that began when Mirmira and members of his lab were at Indiana University. The role of the 12/15-Lipoxygenase enzyme was discovered by Jerry Nadler, MD, Dean of the School of Medicine and Professor of Medicine and Pharmacology at New York Medical College, and Maureen Gannon, Ph.D., Professor of Medicine, Cell and Developmental Biology, and Molecular Physiology and Biophysics at Vanderbilt University, provided a strain of mice used in the study, which allowed for the knockout of the Alox15 gene when given the drug tam

Sarah Tersey, Ph.D., Research Associate Professor at UChicago and co-senior author of the new study, led an experiment in 2012 that was among the first to show that the beta cell could play a role in the development of type 1 diabetes.

This allows us to better understand the underlying mechanisms that lead to the development of type 1 diabetes,” Tersey explained. “This has been a big, altering component of the research where we are focusing more on the role of beta cells rather than merely autoimmunity.”

The research also has intriguing links to cancer treatments that use the immune system to fight malignancies. Cancer cells frequently express the PD-L1 protein in order to inhibit the immune system and avoid detection by the body’s defences. Checkpoint inhibitors are new medications that target this protein, blocking or eliminating the PD-L1 “checkpoint” and allowing the immune system to assault malignancies. The enhanced PD-L1 in the mutant mice accomplishes its intended effect in the new study by blocking the immune system from targeting the beta cells.

The researchers also tried a medication that suppresses the 12/15-Lipoxygenase enzyme on human beta cells in the latest study. They discovered that the medicine, ML355, raises PD-L1 levels, implying that it could stop the autoimmune response and prevent diabetes from developing. It would ideally be administered to people who are at high risk due to family history and exhibit early signs of developing type 1 diabetes, or quickly after diagnosis, before too much damage to the pancreas has been done. Mirmira and his team are starting clinical trials to explore a potential therapy using ML355.

“This work shows that blocking the enzyme in humans can boost levels of PD-L1, which is really promising,” Mirmira added. “With beta cell targeted treatments, we believe that as long as the disease hasn’t advanced to the point of significant beta cell death, you can catch an individual before that process begins and prevent disease development entirely.”

The paper is titled “Proinflammatory Signaling in Islet Cells Promotes Pathogenic Immune Cell Invasion in Autoimmune Diabetes.”